John Kim gave me the link to a new Spirit of the Century campaign page, Dragons of the Yellow Sea, and boy is that cool or what! I read His Majesty’s Dragon and thought the idea of dragons in real life was cool, though the book didn’t grab me otherwise. But the thought of dragons on Jejudo… that’s just delicious. (And those sturdy, clever little island ponies? ‘Yum’ indeed for our scaled friends. 😉

John asked me about possible hooks and tropes for a Korean campaign set in the 1860’s, though he is wisely unconcerned with historical accuracy. This post far exceeded LiveJournal’s max for comments, which is why I moved it here. You know what they say about being careful what you wish for…

Society

Yangban on donkey with Nobi attendants, commoners bowing by the roadside

In addition to taxes paid with rice or other commodities (by the nineteenth century paying in currency was fairly common as well), commoners also paid with labor, working on major state-run constructions like fortifications, and could be drafted into the army. These were all sources of widespread misery, as you can imagine: Overworked peasants dropped like flies from starvation and contagion. If you had money you could pay off the labor tax with cash, and the steady rise of rich commoners was another source of social pressure. Heck, some commoners were actually buying impoverished noble families’ Jokbo (family records) to pass themselves off as nobility–effectively buying stature with cash.

The indentured servants, the Nobi, worked in the noble households and could be bought and sold. An individual or family could also have their free (common, or even noble) status stripped away and become Nobi, usually because they were associated with some major crime like treason. The archetypal story is one where a nobleman is accused of treason and is messily executed, then his entire family are slaughtered or sold into servitude. This status of servitude was hereditary, so this meant effective annihilation for the whole family.

So there are some interesting social pressures in regards to class. There’s the traditional oppressive class system, perpetuated for, oh, easily a thousand years. There’s also resentment building steadily against it, with the growing recognition of the horrible iniquities and the rise of some rich commoners. For the Yangban the new development is a source of alarm and righteous indignation; for the Yangin and especially the Nobi the old system is a source of growing resentment. The historical details are unimportant, but these kinds of opposing pressure could make for some really meaty conflicts. Korea had its share of peasant and slave uprisings, particularly when times were bad with famine and such.

Maybe dragons played a role in such conflicts as well?

You could bring class into play in a number of ways, one of which is the issue of class and dragons. What class of people ride dragons? Many Yangban considered physical exertion beneath them. Chosun was a country that consistently looked down on martial pursuits in favor of scholarly ones, so soldiers, even noble ones (Mushin), were considered inferior to the bureaucrat scholars (Munshin). Still, “Yangban” does mean the “two Bans”–the Munban, which is the bureaucracy, and the Muban, which is the military. Overall I’d imagine the noble-born officers who passed the relevant state exam (the Mugua) would be the most likely candidates for dragon riders.

Of course, dragons can’t be expected to give a fig for human conventions, so I can definitely imagine the pesky creatures choosing commoners or even some slave who was sweeping the yard or carrying loads. Or a bureaucrat who must now lower himself to officerhood. Or even–horror of horrors–a woman! It would actually be better if it were a commoner or slave woman. I can imagine many a noble lady fainting dead away at the idea of her daughter running around with men and engaging in sweaty physical exertion.

Women

The status of women was, well, pretty bad. They couldn’t inherit, had no right to leave their husbands… hell, even remarriage was frowned upon for widows. This was worse for noblewomen because they were more tightly bound by repressive moral expectations. Common women had more leeway, but overall it was pretty severe.

At least if you were born noble it was unlikely you were illiterate, though your education was limited compared to noblemen. Hangul, the letters created for the Korean language, was (and is) immensely easier to learn than Hanja, the Chinese characters used by the elite, so women turned to Hangul for self-expression. The bureaucrat elite looked down on Hangul as Un-mun, the woman’s letters, but many examples of Hangul literature by Chosun noblewomen survive and are highly regarded today.

Kisaeng

Cultural themes

One recurring trope in comical Korean folklore is the plucky, worldly, clever commoner and the boorish, sheltered nobleman. That might be fun to work into the characters, kind of a two-man comedy routine coupled with social commentary.

Another recurring theme throughout history is that the central government is oppressive and uncaring of the people, so the people had damn well better rely on themselves if they want to get anything done. Yet reverence for the king’s person was almost absolute unless he was really, really tyrannical. Mostly it was the Yangban who bore the brunt of resentment.

The local government was sometimes good, sometimes bad, but the central government was almost always seen as corrupt and untrustworthy.

Lee Sunshin

This is a fairly typical hero’s tale in the Chosun era; there’s no stigma for a hero to be accused by the state, since there’s no trust in government. If anything it adds to his heroic status, because he’s made powerful people nervous. The hero’s tale also doesn’t end in revenge and bloodbath like it might in Japan. Yes, the hero was horribly wronged; no, he’s not going to take revenge, rather he’s going to prove his righteousness through heroism or cleverness, which will shame the person who wronged him. The hero will be triumphantly restored if it’s a happy story, and die tragically or leave for greener pastures if it’s a sad one. Either way it’s society that will judge the villain, not the hero him/herself.

Weaponry

Korea never did share its neighbor’s fetish for swords, though they were commonly used. (Korean swords share a superficial resemblance to the katana but were actually very different, and were used differently.) The weapon with the greatest hold on popular imagination was probably the bow. (On a probably unrelated but fun note, check out the Korean Olympic team’s track record in archery.) Jumong, founder of the ancient kingdom of Goguryoh, is a prime example of a legendary marksman. So was Lee Sung-Kié, the founder of Chosun.

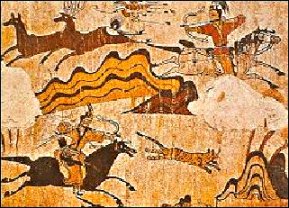

Goguryoh hunters

Of course, there’s no need to dispense with more modern weapons, either. Remember, gunpowder was a Chinese invention, and Korea also received a painful lesson on the power of firearms when the Japanese used them in their sixteenth-century invasion of the peninsula. Within years the Koreans were firing back with guns of their own.

Dragon folklore

Blue and Gold Dragons

Regarding the traditional affinity with water, the king of the sea was called Yong-Wang, the Dragon King. There was also an ancient king (Munmu-Wang in the 7th century, 30th king of Shilla and the first king to unite the peninsula if you want specifics) who had his remains buried at sea so he could rise as a dragon and protect the peninsula from the marauding Japanese. His watery grave is a rocky outcropping in the Eastern Sea (or the Japanese Sea as it’s commonly known outside of Korea), about two hundred yards around. It’s called Sujung-neng, Underwater Grave, or Dai-Wang-Am, the Great King’s Rock.

Another important dragon in Korean mythology is Choyong. He’s one of the seven sons of the dragon of the Eastern Sea, who became the retainer of a 9th century king. Heck, maybe he was even a progenitor of latter-day dragons. Evidently he lived in human form among humankind, though.

The king (Hun-gang-wang, 49th king of Shilla) gave Choyong a beautiful wife, so beautiful that Yokshin, the spirit of contagion, became enamored of her and took on man-form (one version of the story says Choyong’s own likeness) to sleep with her. Choyong, coming home late at night, saw them lying together, but instead of getting angry he withdrew dancing and singing:

On a bright moonlit night in Seoul

I come late from carousing

In my marriage bed

I see four legs.

Two are mine

But what of the other two?

Once they were mine

But they were taken, so what can I do?

Choyong's likeness

Japan

I notice I keep mentioning Japan, so here’s a brief rundown on cultural attitudes: The Koreans traditionally thought of the Japanese as savages, pirates and marauders with no culture or history. (They were wrong, fatally so, but when have neighboring countries ever lacked for mutual prejudice?) With China, the font of all culture and civility (yeah right), as Korea’s traditional patron, the defeat of China by Japan was a huge shock.

Also, the coastal dwellers in particular suffered from Japanese pirate attacks, so there was hostility going on in that direction, too. Then there was the invasion in the sixteenth century during which the whole country suffered. (Imjin Waeran, “the attack of the Puny People in the year 1592”) One common derogatory term for Japanese is Jjokbari, “footpieces,” regarding their distinctive footwear; another is Waenom, “puny bastard(s),” mocking their height.

Wow, that is one LONG post. I tried to tickle the imagination rather than give a history lesson–I’m note sure how well I succeeded.

Hey, I’m really glad you like the idea! Your writeup is very helpful and interesting. I’ve been doing a lot of research and worldbuilding for the game. You would not believe how long it took me to make the geneology of the Korean royal family in the 1800s, and I’m still not done. I especially got interested in the personalities of all the dowager queens!

Hell yeah, it’s a really cool campaign idea. Glad you found my writeup helpful. 🙂 I’ve read your first actual play post, sounds like it was one bad-ass session. Pulp adventure, nineteenth-century Korea style! Heh.

Wow, a royal genealogy… you’re a braver woman than I am. At least you’re not doing the whole five hundred years, now that would be torture. I’m assuming you’re doing this for the international intrigue portion of the campaign? Overall the dude who sits the throne in Hanyang wouldn’t have a huge impact on the lives of commoners on distant Jejudo. Some kings are better, some worse, sometimes there’s internal unrest and heads roll, life goes on.

The dowager queens were some very interesting (and scary) ladies. It’s fascinating to see how women found and held power in such a deeply sexist society. You might want to look at some royal concubines as well, some of them were very intriguing personalities and important power players. Then, my advice is–mix and match what grabs you for maximum mayhem.

Have fun, and I’ll be looking forward to more AP posts!

http://blog.storygames.kr/entry/dragons

Have fun, and I’ll be looking forward to more AP posts!

Thanks! But you should follow the link to “Dragons of the Yellow Sea,” at top, for that, since that campaign was John Kim’s baby.

It’s really great article. I would like to appreciate your work and would like to tell to my friends.